[Salma Elmallah, ERG graduate student]

Every time I encounter an environmental organization, I can’t help but wonder, are they all this overwhelmingly white? I often find myself scanning rooms during talks or workshops and counting the number of minorities. I can usually fit them on one hand. I finally decided to look at the data to see if my firsthand experiences matched the realities of the entire field.

I found a 2014 study by Green 2.0, an initiative focused on racial diversity in environmental organizations, that found that racial minorities constituted less than 16% of boards and general staff of NGOs, government agencies, and grant making foundations, and their positions were concentrated in the lower ranks. As a point of reference, racial minorities made up 38% of the US population at the time of publication. In fact, the only position that minorities were more likely to hold than white people was that of the diversity manager, which only existed at a few organizations.

Organizational leadership often self-reported that the biggest barrier to a more diverse workplace was a lack of minority and low-income applicants. At the same time, only a quarter of organizations in the study offered paid internships, which candidates from low-income backgrounds consistently cite a barrier to entry and advancement. Other minorities interviewed cited barriers like the absence of good mentorship, not being listened to by coworkers, and an institutional attitude that gender diversity - the gains of which primarily went to white women - was an adequate substitute for racial and class diversity.

What does it mean for environmentalism if the people shaping it are mostly white and middle class? For one, an organization’s prioritization of issues stems partly, if not heavily, from the people that compose it. Only 41% of NGOs interviewed in 2014 were likely to support adding issues of interest relevant to low-income or minority communities to their agendas. Employees reported across organizations that attempts to partner with local environmental justice groups were limited. Of the NGOs interviewed, people of colour were especially underrepresented in key decision-making positions, composing less than 5% of board slots and about 12% of leadership positions.

Environmental justice and grassroots organizations often perform better along diversity metrics. Mainstream environmental organizations on the national level benefit from having close ties to industry and government, oversight and monitoring capabilities, and strong, independent research arms. As long as mainstream groups have access to resources and influence that grassroots or environmental justice organizations do not, issues that impact low-income or minority Americans will receive limited attention on a funding and political agenda.

At some point during the long stretch between pitching this blog post idea to one of ERG’s patient and enduring blog editors, Anushah, and actually writing it, I was riding BART and noticed anti-immigrant ads plastered throughout Civic Centre Station. When I see bad things, I like to Google everything about them. So I looked up Progressives for Immigration Reform, the organization that funded the ads, and found out that one of their leaders almost succeeded at a 2004 effort to make anti-immigration candidates compose the majority of the Sierra Club’s board. An interview with a Sierra Club leader conducted around the time of the attempted takeover mentions that no red flags were raised about anti-immigrant candidates until 2004. This is strange because it was publicly known that one of the candidates who already had a Sierra Club board appointment during the takeover had also been sitting on the board of an anti-immigration organization for at least two years.

I filed this discovery away in my head until I finally got around to writing this blog post, when the Sierra Club’s near-xenophobia resurfaced in my memory. I’m not sure how the Sierra Club came so close to having an anti-immigration majority board. It’s possible that, when your organization is dominated by a singular demographic, it becomes harder to recognize such seemingly obvious red-flags. They may never have had to recognize how racists mask their rhetoric with a resonant political message - like the “war on terror”, or being “tough on crime”, or, even, “the fight against climate change” - so voting for a candidate that relates environmental issues to immigrants and overpopulation doesn’t seem transparently xenophobic (even though discussions of population control have an undeniable racist history). Writing this blog post showed me that mainstream environmental organizations are in fact just as white and upper class as I was seeing. This comes at the expense of opportunities for individual employees, and the issues that are deemed important.

When I started this post, I was thinking about what a career looks like for someone whose demographic isn’t well represented in major environmental organizations. Maybe selfishly, I was thinking about what these statistics mean with regards to my imposter syndrome, or a sense of isolation, or career progression. I realized that the demographics of the environmental field can have implications for me, both as a prospective employee and as someone impacted by the agendas and policies. A discussion of environmentalism in the United States is incomplete if it doesn’t address how a lack of diversity informs how we define environmental causes, and how environmental causes can be mobilized.

|

| Photo courtesy of Green 2.0 |

Every time I encounter an environmental organization, I can’t help but wonder, are they all this overwhelmingly white? I often find myself scanning rooms during talks or workshops and counting the number of minorities. I can usually fit them on one hand. I finally decided to look at the data to see if my firsthand experiences matched the realities of the entire field.

I found a 2014 study by Green 2.0, an initiative focused on racial diversity in environmental organizations, that found that racial minorities constituted less than 16% of boards and general staff of NGOs, government agencies, and grant making foundations, and their positions were concentrated in the lower ranks. As a point of reference, racial minorities made up 38% of the US population at the time of publication. In fact, the only position that minorities were more likely to hold than white people was that of the diversity manager, which only existed at a few organizations.

|

| Photo courtesy of Green 2.0 |

Organizational leadership often self-reported that the biggest barrier to a more diverse workplace was a lack of minority and low-income applicants. At the same time, only a quarter of organizations in the study offered paid internships, which candidates from low-income backgrounds consistently cite a barrier to entry and advancement. Other minorities interviewed cited barriers like the absence of good mentorship, not being listened to by coworkers, and an institutional attitude that gender diversity - the gains of which primarily went to white women - was an adequate substitute for racial and class diversity.

What does it mean for environmentalism if the people shaping it are mostly white and middle class? For one, an organization’s prioritization of issues stems partly, if not heavily, from the people that compose it. Only 41% of NGOs interviewed in 2014 were likely to support adding issues of interest relevant to low-income or minority communities to their agendas. Employees reported across organizations that attempts to partner with local environmental justice groups were limited. Of the NGOs interviewed, people of colour were especially underrepresented in key decision-making positions, composing less than 5% of board slots and about 12% of leadership positions.

Environmental justice and grassroots organizations often perform better along diversity metrics. Mainstream environmental organizations on the national level benefit from having close ties to industry and government, oversight and monitoring capabilities, and strong, independent research arms. As long as mainstream groups have access to resources and influence that grassroots or environmental justice organizations do not, issues that impact low-income or minority Americans will receive limited attention on a funding and political agenda.

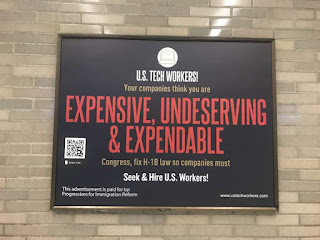

At some point during the long stretch between pitching this blog post idea to one of ERG’s patient and enduring blog editors, Anushah, and actually writing it, I was riding BART and noticed anti-immigrant ads plastered throughout Civic Centre Station. When I see bad things, I like to Google everything about them. So I looked up Progressives for Immigration Reform, the organization that funded the ads, and found out that one of their leaders almost succeeded at a 2004 effort to make anti-immigration candidates compose the majority of the Sierra Club’s board. An interview with a Sierra Club leader conducted around the time of the attempted takeover mentions that no red flags were raised about anti-immigrant candidates until 2004. This is strange because it was publicly known that one of the candidates who already had a Sierra Club board appointment during the takeover had also been sitting on the board of an anti-immigration organization for at least two years.

|

| Photo courtesy of SFGate |

I filed this discovery away in my head until I finally got around to writing this blog post, when the Sierra Club’s near-xenophobia resurfaced in my memory. I’m not sure how the Sierra Club came so close to having an anti-immigration majority board. It’s possible that, when your organization is dominated by a singular demographic, it becomes harder to recognize such seemingly obvious red-flags. They may never have had to recognize how racists mask their rhetoric with a resonant political message - like the “war on terror”, or being “tough on crime”, or, even, “the fight against climate change” - so voting for a candidate that relates environmental issues to immigrants and overpopulation doesn’t seem transparently xenophobic (even though discussions of population control have an undeniable racist history). Writing this blog post showed me that mainstream environmental organizations are in fact just as white and upper class as I was seeing. This comes at the expense of opportunities for individual employees, and the issues that are deemed important.

When I started this post, I was thinking about what a career looks like for someone whose demographic isn’t well represented in major environmental organizations. Maybe selfishly, I was thinking about what these statistics mean with regards to my imposter syndrome, or a sense of isolation, or career progression. I realized that the demographics of the environmental field can have implications for me, both as a prospective employee and as someone impacted by the agendas and policies. A discussion of environmentalism in the United States is incomplete if it doesn’t address how a lack of diversity informs how we define environmental causes, and how environmental causes can be mobilized.

No comments:

Post a Comment